|

TENET (Thematic Analysis): One for Posterity

Written by Kev You can listen to this article below if you prefer or by clicking HERE! Christopher Nolan… the guy needs no introduction at this point. He is the premiere blockbuster hitmaker for the past 12 or 15 odd years now. Amidst the height of his pop culture powers, he has become oddly divisive. I say oddly, because from any interview I’ve ever seen, nothing about the guy’s attitude or manner invites anything inflammatory. He doesn’t have a wild ego or outlandish persona that we typically expect to rub people the wrong way. I can see his commitment to physical film over digital, or practical effects over CG, coming across as a little snobbish. Still, when the guy Is relatively soft spoken and humble when asked to speak on his own impact as a filmmaker, it’s hard to understand how “somewhat snobbish” translates to infuriating for many. Are there other factors that make him frustrating then? His movies do welcome a fair bit of nitpicking. Marketed as “thinking man’s blockbusters” or “cerebral films”, they practically beg the audience to prove they aren’t as smart as they claim. These designations for his films seem to be attributed by the internet more than Nolan himself though. I have seen him say many times (usually due to a leading question from the interviewer) that he enjoys “challenging the audience” or “respecting their intelligence”, but I’ve never seen him describe his movies as “smart” or average blockbusters as “dumb”. Yet his movies can often be judged more as documentaries than works of fiction. Any scientific inaccuracy can invalidate the entire narrative for many. Nolan often strives for realistic depictions to be sure, but only up to the point where they don’t limit his storytelling. For just one instance of Nolan sidelining the science to create a better film, you can read this article from Gizmodo. The article also demonstrates how his film’s scientific ambitions are often a construct of the internet as much as of the man himself. Nolan is a story teller first, a cinematic visionary second, and a science professor last. Any scientific accuracy his movies have should be considered the cherry on top, not the main course. Now the issue of scientific accuracy, or lack thereof, is just one of many recurring criticisms that sink Nolan in the eyes of many. His films are too long, full of clunky exposition, sloppy editing, and poor sound mixing. Another common complaint is that his characters are paper thin, or at the least, get lost at the expense of his labyrinthian plots. This question of character is something we’ve discussed on the podcast and you can check those discussions out here and here. I personally find these criticisms range in validity, but there’s no denying they exist in the discourse around his films. Then along comes Tenet… His latest effort is easily his “Nolaniest”. It’s almost as if he took every criticism to heart, then actively threw them out the window to spite his detractors. As I sat in the theater, hyper aware after our podcast conversation, I cringed to learn the main character’s name was “The Protagonist”. Not so much because it bothered me, but because I knew this movie was already going to be sunk for many. Throw on top of it a core concept so convoluted, that even for a staunch Interstellar apologist such as myself, the only defense I can muster is, “it either works for you or it doesn’t.” A science documentary Tenet is certainly not. Don’t misunderstand me though. I said above that “it’s almost as if” to show how we might perceive his intention when making the film. I feel the more likely explanation is that Nolan doesn’t care about those criticisms and made the film he wanted to make. This sticking to artistic guns is something we would applaud in most other creators, but it can be truly aggravating when it come to Nolan. Perhaps we like the idea of the auteur pursuing a vision but consider it a little unfair when they get to do so with a $200-million-dollar budget. We complain that too many big budget affairs are formulaic and boring, then solve the ones that aren’t by prescribing them by-the-numbers solutions. It may be that a backstory for The Protagonist (or a proper first name even) cures what ails Tenet, or maybe not. Either way the final product of Tenet is what it is. So… with this long of a preamble, what is the purpose of this article? It is not to defend the science of Tenet or explain every plot-hole. It’s also not to dissect every character to defend their lack of backstory or fabricate my own for them. Instead I want to ask the reader to accept the concept of inversion for what it is, and the characters for what we are given. If we concede Nolan these elements, does Tenet give us back something worthwhile? While many can boil their critique down to “Nolan went to far up his own *$$”, I have seen a fair number of reviews willing to give Nolan some grace. It seems that even if we can reach this point, there is still a feeling that Tenet is ultimately hollow, or “all sizzle and no steak”. A reviewer for Variety.com put it this way,

“Again, his musings are rooted more in physics than philosophy or psychology, with the film’s grabby hook — that you can change the world not by traveling through time, but inverting it — explored in terms of how it practically works, not how it makes anyone feel… "Tenet” is not in itself that difficult to understand: It’s more convoluted than it is complex, wider than it is deep, and there’s more linearity to its form than you might guess”.

I can sympathize with this read on the movie, and I would honestly say I identified with it as the credits rolled…

I’m realizing I still haven’t explained the purpose of this article have I… my goal is to explore the themes of the film and questions it poses for myself. Half due to the film’s convoluted nature and half due to the surrounding context of the filmmaker previously described (and I suppose one more half due to many not seeing the film as a result of COVID… that’s 3 halves… maybe I am drinking too much Nolan Kool-aid), I have hardly seen any critic dive into the film’s themes in any substantive way. They allude to the movie’s superficiality without really explaining how it falls short in exploring its themes. After all. the themes are fundamentally deep on paper. The two biggest that I identified, and that we will examine, are FREE WILL and POSTERITY. If the film did fail to properly explore these themes, then that is a critique I anticipate even Nolan himself would find valid. After all, he himself did write in his film THE PRESTIGE. Free Will

***Spoilers! Only continue reading if you've seen the film***

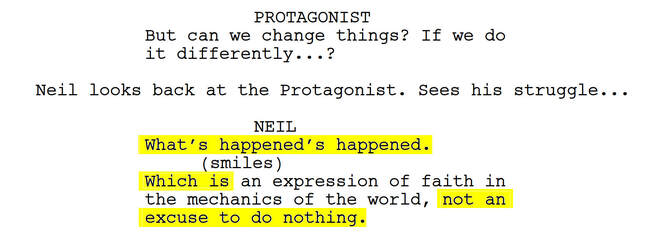

We will begin with what is clearly one of the film’s biggest themes. I suspect we can’t get away exploring what it says about free will, without at least partially explaining the mechanics of inversion. You see, it becomes clear as the film progresses, that time inversion all takes place on a single timeline. If you decided after the fact to invert and try to change something you did, it is ultimately moot because you were already present attempting to make the change the first time. One of the best examples of this is shown from the main antagonist Sator’s perspective. He waits for details of The Protagonist’s (will be denoted as TP from now on) heist, then inverts to go back as an ace in the hole. By waiting till the end, he has knowledge to supersede any sleight of hand TP may attempt and ensure he obtains the plutonium (which is really the algorithm, for the rest of this article we will call it “the 241”… Oh, and we can also call it what it is, a macguffin… actually it’s 1/9th of a macguffin, so it’s a horcrux). Where Tenet becomes interesting is in how this strategy plays out differently than it would in other time travel films. Normally, if Sator initially lost the 241, then went back and obtained it by knowing the past, this would create an alternate timeline. Tenet makes clear this is not how it actually worked by showing it from TP’s perspective first. We see that there was no first heist where Sator never showed up, then a second version where he magically knows how to get the 241. Inverted Sator arrives during the initial heist and successfully obtains it. The mechanics of this are further driven home when we realize that an inverted version of TP was driving the Saab that un-crashed in time to facilitate forward TP’s attempted sleight of hand. So even though Sator inverted after the heist, and then TP inverts after Sator, they are both present at the same point in time the first time (by the way, it’s not lost on me how annoying explaining this stuff on paper makes Tenet). What does this imply about the capabilities of inversion though? Seemingly it can’t be used to change the past, because you were already there attempting to change it and failed. At best inversion gives you an advantage but it is by no means a guarantee when both sides are utilizing it. So, it would seem inversion is pretty limited when compared to your usual time travel mechanic. These factors have led many to the conclusion that there is no free will in the world of Tenet. The phrase frequently recited “what’s happened’s happened” paired with inversion’s seeming inability to change the past lends to this conclusion. While this can be unsatisfying from a philosophical standpoint, it can be even more disappointing from the narrative’s perspective. If the characters have no ability to change what’s happened, doesn’t it make the entire ending anti-climactic? It would seem Nolan even understood this issue, speaking through TP when he says:

This means we already know the good guys win. Not just in “the good guys always win” sense, but we realize it’s baked into the rules of Tenet’s world. Still, when the creator nearly breaks the 4th wall to point out they understand this concern, I think it warrants a little prodding to see if there isn’t a more complete interpretation. I think the only way to see if this more complete interpretation exists is by examining the main characters and their actions/mind sets. Of course, it makes the most sense to start with TP.

TP is unique among the film’s characters (perhaps it’s the reason he deserves to be the protagonist) because he consistently attempts to enact his will. Some of this is depicted as a naïve misunderstanding of inversion mechanics, but other times it manifests in deliberate decisions he makes. This character trait is established from the very beginning with the Opera siege. His mission is simply to retrieve the 241 (not yet knowing what it is) and extract Tenet’s undercover operative. The bad guys have rigged the auditorium to explode though and sacrifice the audience as collateral damage to cover their tracks. Having successfully secured his mission objectives, TP makes a personal call to risk going back into the auditorium to retrieve the explosives and save the crowd. This almost costs him his life, but he is saved by a mystery man we later learn is Neil. Regardless, the point is that TP made a decision he didn’t have to make which resulted in saving lives. Also interesting is the fact that the “admittance test” given him by Tenet is based on a choice. He is fit to be brought into the organization because he made the choice to sacrifice himself rather than give up his teammates. But Tenet also know about his initial decision to go off mission and risk failure to dispense the bombs. As we learn more about how Tenet operates, this may seem a little bizarre. After all, shouldn’t an organization from the future that has knowledge of future events just seek operatives that simply follow orders? A Tenet member would not need the capacity to make tough choices, they can just receive the objectively correct course of action to follow from the future. And yet, this is not how Tenet functions at all. We learn one of their core tenets (I had to do it once) from Priya.

This intentional concealing of information takes place repeatedly throughout the movie. On the one hand, it’s a convenient trick for Nolan that allows him to withhold answers to the film’s mysteries until he wants them revealed. Diegetically, it allows the Tenet organization to maintain the free will of their operatives. They merely give parameters to guide their mission, then allow them to fulfill it as they deem fit. You may read what I just said about Tenet’s motives and think, “no it’s to prevent counter intelligence!” You are correct that it is to avoid leaving a trail of intel the future can access to know their plans, but this taps into the idea of “posterity” which we’re not quite ready to discuss. For now take my word that it accomplishes both.

Consider TP’s decision during the Tallinn heist that we already described before. More specifically, consider Ives’ reaction to TP’s decision. He very clearly does not approve, terming it “cowboy shit”. He also captains a team and presumably pulls rank, yet he lets TP go after Sator when he clearly isn’t prepared to handle inversion. Of course, we learn TP is intended to lose the 241 to Sator so they can steal the completed algorithm later, but from TP’s perspective his ignorance allowed him to make a genuine choice to pursue it. I think it’s also safe to assume Ives wasn’t privy to the plan, since even Priya didn’t know about the Stalsk operation until TP told her. All of this highlights how perspective on free will changes depending on the perception of time. Things look deterministic from the future, but dependent on decisions from the present. This is how maintaining the agency of their operatives plays out for Tenet. There is one more complication we find due to inversion we haven’t examined yet. What happens when you arrive at the desired outcome thanks to inversion, but something undesirable had to happen to achieve it? This is exactly what happens at the end of the film with Neil. An inverted Neil unlocks the interior vault that allows TP and Ives to procure the algorithm but is shot dead in the process. Tenet achieves their goal, but with a very undesirable side effect. This begs the question, if Neil and TP decide Neil shouldn’t have to die, can they roll the dice and not have him invert? This of course would create one of many potential “Grandfather Paradoxes”, which is a concept the characters are aware of. Still, the question remains – is it possible to attempt a Grandfather Paradox, or is Neil compelled to follow the course of fate? I think Neil delivers one of the best lines in one of the film’s best scenes. TP and Neil’s farewell brings a much-needed warmth to their relationship, but also reveals how the rules of the film work.

You see there is nothing stopping them from getting greedy and testing a Grandfather Paradox. Neil in particular works to prevent them because he doesn’t desire to find out what happens when one occurs, but there’s no reason to think they couldn’t create one to save Neil. This is the culmination of why Tenet seeks agents who will make the hard decision and sacrifice themselves for the greater good. With inversion it is tempting to put confidence in your understanding and the near omniscience it gives you of the past. It can be tempting to assume you can fix every problem and facilitate a perfect solution that gives you everything you want. If someone or something is hindering your plans, just go back and take them out before they’re a problem. Maybe the paradox works out in your favor. Neil understands that there is no perfect reality. His sacrifice is necessary to save the world and he makes the decision to place the survival of other’s above his own. Just because he has faith things played out the way they were supposed to, does not mean they couldn’t play out differently if he’d acted differently.

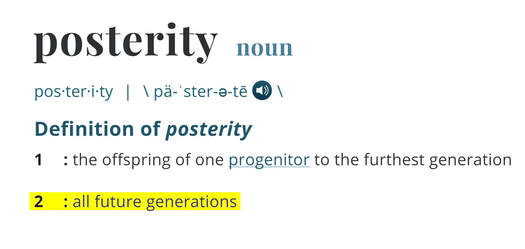

So how does any of this pertain to our reality? What does this indicate, if anything, about free will in a world that doesn’t have inversion? I will answer this question, but I think it best I finally break down the idea of “Posterity” before bringing it all together. After all, the concept of inversion is fantastical and hard to map to real life, but the way the film depicts posterity I believe maps very cleanly. So… what is posterity? Posterity

I found the use of the word in the film interesting. After all, they could have just used the term “the future” but I think “posterity” is much more descriptive. It speaks to the human element of the future. It makes the future as personal as is possible. After all, how much time do we really spend thinking about our distant descendants? In my experience, my compassion and energy only goes up to my grand-parent’s generation, and I anticipate it will only trickle down to my great-grandchildren (if I live long enough to meet them). We think of future generations in general terms, but it is hard to feel too much for them because we will never personally know them.

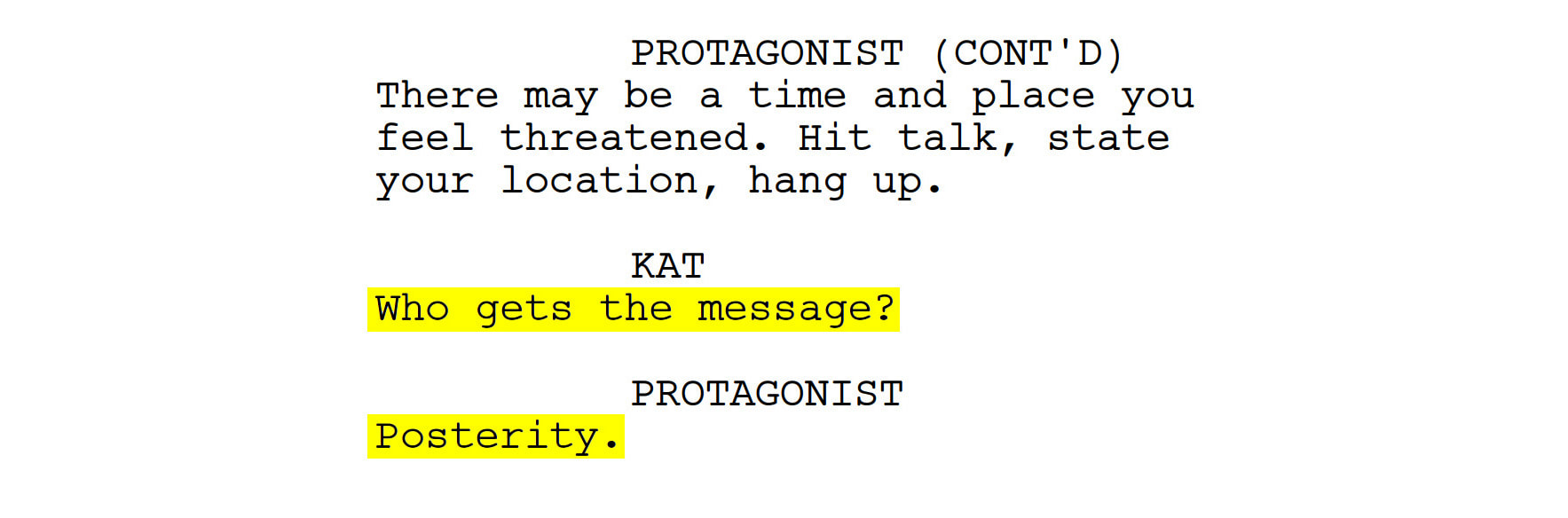

The rules of inversion change this. The future can now communicate with the past and they make clear they don’t like us much. It’s hard to blame them though, as it turns out we left them an abused and unsustainable planet. This sets up the framework for the film’s conflict. Sator and TP are really just proxies for the true battle being waged between the future generations and the present. Between this generation and posterity. This communication between present and future is of course possible because neither generation must perceive the passing of time. If Sator sends an email, the future receives it instantaneously, regardless of how far into the future they are (technically they have access to every email he ever sent instantaneously). Conversely, if the future inverts a message for Sator, he can retrieve it instantaneously, not perceiving the time the inverted package spent travelling backwards. This is a huge advantage to both viewpoints as they can adjust plans quickly based off the information they receive from one another (facilitating temporal pincer movements). We see TP begin to leverage this method of communication at the end of the film.

TP realizes he can protect Kat without having to follow her. He will retrieve her message instantaneously (from his perspective) in the future, then invert and arrive to save her instantaneously (from her perspective). This is exactly what happens when he saves her from Priya, who attempts to clean her up as a loose end. Overall, inversion gives us a fun way of literalizing the fickle way we perceive communication between generations.

Of course, without inversion we cannot send communications TO the past, but we do receive communication FROM the past the way the movie depicts! Whether the history was recorded a hundred years ago or a thousand, I can pull it up on google right this instant. I don’t perceive the extra time the thousand year old history had to travel to reach me either. The only reason I know the one history is much older is because I was told it is. In ancient times, it was hard to preserve a message well enough that it could survive to posterity. Furthermore, unless you were a king, explorer, or someone else of supreme consequence your story was likely lost to time. You may have had wisdom you desired to pass down, but you had no way to get it to your distant descendants. This has totally changed in the digital age. We are the first generation of humans who have the capability to communicate with posterity en masse. Every facebook status, tweet, blog entry, youtube video, and Instagram post could feasibly last forever (you know, assuming the internet doesn’t explode, or social media companies don’t pull down all your content… just go with me on it). We are all communicating directly with future generations, but how often do we consider this? Would the message of your podcast change if you were intending it for posterity rather than to address the hot button political topic of the day? Your descendants will not have to wonder what you were like or what you stood for. If your online footprint is big enough, they will hear from you directly! I myself had literally never considered this until thinking about the film. It’s made me realize I hope I’m proud of the message I’m sending to far more than just my great-grandchildren. Alright let’s finally get to the point…

With all this in mind… what does Tenet have to say to the generation in which it was released about these topics? Unfortunately, like nearly all of Nolan’s movies, it leaves it open. It is hard for me to say definitively that the characters in the movie had free will, as he leaves enough in there to suggest the outcome was predetermined. Even if every event of the movie played out according to the will of future Protagonist, was he fated to orchestrate it the way he did? Could he have decided to let Sator succeed and potentially wipe out humanity? The film makes the case for both possibilities.

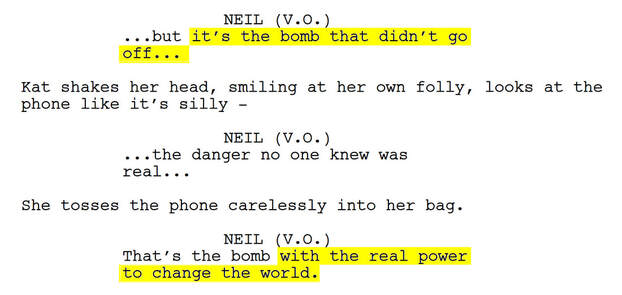

I’ve noticed the tendency for modern film analysts to criticize open ended films like this as “lacking a point of view”. Unfortunately we want our media to tell us WHAT TO THINK instead of giving us tools that simply LET US THINK. The reality is that the idea of free will lies somewhere in the middle for modern humans. Yes, we have the capability to make decisions, but many decisions we wish we could make lie outside our power. We don’t get a say in the nation, genetic advantages/disadvantages, time period, or many other factors we are born into. We can choose how we see fit, but the choices available to us are constrained. This can be frustrating, but it doesn’t do us any good to linger on the fact. It also doesn’t mean that the decisions we make are insignificant, even if we feel like we have no capability of changing the future. Whether you have faith in the mechanics of the world, or utter distrust, it is not an excuse to do nothing. As for posterity, I think Tenet helps us grasp the reality of our relationship with it more completely. A phrase I hear increasingly in modern discourse is - “Don’t end up on the wrong side of history.” When we say this, we are taking a similar role as “Posterity” in the film. They know previous generations were “on the wrong side of history”, harvesting the planet’s resources unsustainably for short term profit. Since they are literally capable of communicating with the past through inversion, they let them know this fact. I understand the sentiment when we use it in real life, but ultimately I don’t like the phrase, as we don’t know the future for a fact. We actually try to limit the free will of others when we say that. We’re trying to discourage them from making the choice they see fit, by supposing we already know the better choice. Just follow what we’re telling you… and it will work out best for all of us. Free will means the capacity to make imperfect decisions. It means being allowed to face the consequences of imperfect decisions. The one decision I didn’t mention in my analysis, was Kat’s decision to shoot Sator before receiving the all-clear (Mainly because I still haven’t fully decided what I think it means. I’ll still risk an interpretation here though because I think it’s applicable). It was a short sighted and selfish decision that could have cost the world, but she couldn’t overcome all the pain and anguish that fueled the action. In the same way, we are free to make short sighted and destructive decisions. Maybe we get lucky like Kat, and the decision doesn’t create collateral damage for others, but let’s try to think further ahead before we act. Consider one of the last lines we hear in the entire movie.

Typically we forge ahead and wait until the problem boils over to address it. Conversely, we may not even perceive all the tiny decisions we make that prevent the problem arising in the first place. We may think the catastrophe is the cause, and our efforts to quell it is the effect. But perhaps our inaction is the cause, and the catastrophe is the effect (probably smart not to introduce another weighty concept at the end of your essay… someone else will have to write the essay that does justice to the film’s reversal of cause & effect). We assume TP had no other course but to succeed according to the events of the film, but perhaps he only had that course because he decided to act in the first place.

Conclusion

It is distinctly possible this article quit making sense awhile ago. I kind of blacked out for the last couple pages, so hopefully I presented my thoughts on the film coherently. Regardless of my proficiency in doing so, I believe Tenet warrants this level of analysis. It is hard for me to deem the movie a failure when it has been so successful in provoking my brain to think. Perhaps it was a less enjoyable 2 ½ hours spent viewing than your typical Marvel movie, but I think it was a far more enjoyable 10, 20, 30 (who knows how many at this point honestly) hours spent thinking afterward. Hopefully I’ve sparked a new angle for you to think about it today. Like I said, this type of thematic analysis is what I feel like was missing from all the discourse on the film thus far. I appreciate Christopher Nolan for swinging for the fences with Tenet. I don’t believe he makes hollow films that are only about the spectacle or a puzzle to solve. We might make the point of Inception whether the top falls at the end, but Nolan himself has stated the point is Leonardo DiCaprio’s character doesn’t care. I think Tenet has thematic depths on this level as well. It was daunting to get my thoughts on the film down on paper, but regardless of my success, I’m glad I made the decision to try.

3 Comments

Metal Gear Solid V: My Key to Understanding Kojima Written by Kev (Originally posted: 9/11/17) I’m going to start off by saying this… I love Metal Gear Solid V. It’s not an ironic love either, I just legitimately think it’s incredible as a stealth game, a Metal Gear Solid game, and even in its narrative. I couldn’t always say that though. It’s been a long road to arrive at my current understanding of the game and appreciation for it. This article is meant to look at MGSV itself, Kojima’s thought process while making the game (as if you can ever know what anyone is thinking, trying to decipher Metal Gear Solid games is inseparable from deciphering Kojima’s mind), and how I fell victim to the internet’s depiction of the game. ***Spoilers*** Do not continue if you haven’t played or seen through the game’s ending. Also, before going any further I want to link some articles that helped shape my feelings on the game. If you haven’t played the game in a while, or are fuzzy on the narrative, then I definitely recommend reading these before continuing. This article: metal-gear-solid-v-the-boldfaced-lie/ breaks down the twist-ending and the character of Venom-Snake. This article: mgs5-unfinished-s-entirely-point/ analyzes whether the game was truly unfinished and looks at the larger context of the player’s relationship to the series. I aim to bring something new to the conversation about this game, but I can be honest that accomplishing my goal will be building on the concepts those authors put forward. If it seems like this is a lot of work to understand a game, it’s because it is. But frankly, understanding an MGS game takes work. One playthrough is often not enough, neither is one take on its themes. To be honest though, this aspect of MGS games is one that I only recently began to realize. Watching my older brother play the first Metal Gear Solid when I was 6 years old was fascinating, but to be sure I understood very little of what I was seeing. Playing through Metal Gear Solid 2 and 3 my freshman year of high school was even more fascinating, but little did I know I was still only grasping a portion of what Kojima was conveying. I was as confused as anyone about the convoluted plots MGS is famous for, and I thought the fun was in unraveling said plots. And there certainly is fun to be had doing that, but the political intrigue and beat to beat story sequence has never been the point of MGS games. The plot details are not the point, because they are not what Kojima is interested in (I know you’re about to bring up 90 minute cutscenes, novels worth of codec dialogue, and nanomachines… but Kojima’s contradictory nature is a big part of what makes him compelling. If you’re not on board with it, his games probably aren’t for you.) Rather, Kojima’s interest is in conveying themes and broader concepts to the player. I believe he first chooses the theme he’s trying to communicate, then fits all of his characters and plot in place to depict that theme. This is why retcons and bewildering character motivations don’t seem to bother him: they’re worth it if he feels like they build on the theme he’s communicating for THAT SINGULAR game. Now, Kojima utilizing thematic storytelling is not news. But it was to me, in the sense that I had never prioritized the thematic angle when sitting down to think about his games. Furthermore, I had to learn this before I could find my current appreciation and attitude towards MGSV. If you, like me, were unfamiliar with the themes in these games, this article: legacyofmgs2/ I think gives a concise summary of the core theme of MGS2. If you want an extremely deep dive, look here: MGS2/DOTM. To be sure, these are the kinds of things Kojima thinks about when designing his games, and I think he gives them priority over plot details. So, what are the themes in MGSV then? In my estimation they are REVENGE and PAIN (although to be certain there are more, like LANGUAGE and IDENTITY, but they will not be my focus). I, like so many, bought into the notion that MGSV would depict Big Boss’ turn to the dark side in an epic and conclusive fashion. We would see something SO messed up happen to him that he would have no choice but to *SNAP* and go full on totalitarian mode. Oddly, we wanted to be able to sympathize with his fall and say, “well of course he had to turn evil, didn’t you see what Skull Face did to him!?” Then we could go on a murderous rampage, blow away Skull Face & anyone who complied with his plan, and ride off into the sunset guilt free. The blame for the evil we commit as the players would be placed on Big Boss as the bad guy, and Kojima for making us play as the bad guy. Easy, peasy, fresh, and breezy… and man would it have felt satisfying. There would be a few problems if Kojima had taken the game that route though. It would have given a very shallow and dishonest depiction of revenge. Rarely does bloody revenge make things simple, and even more rarely does it actually leave the one carrying it out with lasting satisfaction. I believe the classic revenge trope has skewed the perception of revenge for many of us who have never truly experienced it, or been directly affected by its consequences. In most revenge movies, once the hero whose family (or dog) was murdered has finished wiping the last of the evil men who did it from the planet, they begin walking away while a FAT guitar riff starts playing. In the best revenge films, they rigged the bad guy’s compound to blow so they can continue to walk away without looking at the immense explosion behind them. Then the credits roll, and we as the audience feel good since the bad guys, “got what they deserved!” Django Unchained is one my favorite movies, but since Tarantino intended it as a classic revenge flick, its depiction of revenge is very shallow. Django and the audience get to ride off with our conscience in-tact, since the bad guys DEFINITELY deserved what they got. But, would killing off all the people who wronged you, truly heal your wounds and leave you off for the better? Did Russia’s treatment of Germany in the decades after World War II repair all the atrocities Germany commit in Russia during the war? Did it truly help the Russians who carried out that revenge in the long run, or their children who they would pass that baggage onto? The desire for revenge is natural and understandable, but it’s debatable if successful revenge can truly bring healing to those seeking it. I believe Kojima wanted to present a more nuanced examination of revenge than the one we get in movies like Django. MGS games are over-the-top to say the least, but Kojima is always trying to impart his players with some principal that applies to their actual worldview. In my opinion, I don’t think Kojima would allow his game to communicate that revenge is a desirable and healthy end goal. Satisfying revenge requires a bad guy who deserves it, but Kojima has rarely depicted his villains in that straight forward a manner. His bad guys usually have shades of grey, often with commendable goals, but sought after in misguided ways. Just as healing from tragedy is a commendable goal, with revenge being a misguided way of reaching that goal. After all, if you dig into the audio files, you’ll find that Skull Face had totally valid reasons for his fall. Growing up in Eastern Europe during and after WW2, his family and culture were intentionally obliterated by both the Nazis and Soviets. Then, he was forever disfigured when the factory he worked in was bombed by the Allies. This gave him good reason to hate both the East & the West. His language, face, and identity were all taken from him. Did the evil course this led him to, truly heal all that damage? Would eradicating the English language give him back his native language and the culture he lost? Of course not, but Skull Face became proficient at wreaking havoc he deemed justified none the less. He is the clear example of what happens when revenge is sought above all else, justified or not. From the players perspective, Kojima laid the foundation for seemingly justified revenge in Ground Zeroes. I don’t know many people who weren’t ready to stick it to Skull Face after that game. I know I certainly was. Kojima had to pull the rug out from under us though to get us to reflect on what that revenge would mean. What it would mean not only for Skull Face (who would be dead) or his men (who will likely be killed in the crossfire), but also for Big Boss’ soul and the fate of the men he is leading (who will also likely be killed in the crossfire, or persuaded by their legendary leader into a belief that revenge is a worthwhile pursuit). Most importantly of all, what would this mean for us as the player as we rabidly seek revenge? Kojima doesn’t want us to be able to pin all this killing on Big Boss and Skull Face, and that is where the twist regarding Venom Snake comes becomes integral. I believe Venom Snake acts as both his own individual character AND as an avatar for us as the player. He is both nobody and somebody (again I recommend you read the article at the top as they make a compelling case for this). He makes his own decisions throughout the game that prove he is independent from Big Boss, able to carry out his own will, even if only to a limited extent. At the least, he is not the perfect body double of Big Boss that Zero/Ocelot sought to create, who would think and act exactly as Big Boss does. He is also the character we are to relate to, because we control the heroes in these games. In previous more linear installments, we may not have had as much control over what Snake did regarding the plot. So, it was easier to embody Solid or Naked Snake as the character was guiding where we ultimately ended up. Kojima doesn’t want us to identify as one of the Snakes though, he wants us to learn from them, so we can carry those lessons and make our own decisions. When Solid Snake or Big Boss make a bad decision, we need to learn from that mistake, not write it off because we are blinded by how awesome they are! In this way, Venom Snake also depicts someone we should strive to be. Despite all the ways he was manipulated and altered without his consent, he didn’t lose his identity or capability of making choices apart from the ones Big Boss would have made. In the same way, we the player are capable of making decisions apart from Big Boss. So, even if the plot thus far is trying to catalyze us into seeking bloody revenge, Kojima would like us to think for ourselves. If we assess revenge is not the best resolution, he is trying to get us to a place where we would choose not to seek it. Most players never reflected on the story to this extent though, already too outraged at the anti-climax and fact they were denied their satisfying revenge. This is where the brilliance of the PAIN concept comes into focus, specifically phantom pain. According to the Mayo Clinic, “Phantom pain is pain that feels like it’s coming from a body part that’s no longer there. Doctors once believed this post-amputation phenomenon was a psychological problem, but experts now recognize that these real sensations originate in the spinal cord and brain.” MGSV plays this literal phantom pain notion for all it’s worth, with Kaz constantly referring to the limbs that both he and Venom lost during Skull Face’s raid on Motherbase. Kaz believes that completing revenge on Skull Face will be the only way to relieve this phantom pain, and he tries to convince Venom of the same. In truth, the phantom pain is the fact that things will never go back to the way they were. The brotherhood of a “military without borders” (Military Sans Frontieres (MSF)) concept was what was truly lost. Motherbase was the limb taken from them, and throughout the game you replace it as Venom, but it can’t stop the continual ebb of pain. Kaz is in denial that the dream he and Big Boss tried to create is gone, because the “military without borders, allegiance, or ideology” had a faulty foundation that could never last. Killing Skull Face and creating a new Motherbase cannot change the fact that the dream has been exposed and destroyed irreparably. Big Boss and Kaz refused to acknowledge the fact that it is impossible to truly be an army without ideology, or simply keep war to a business. If you are hired and fight for a certain government or organization with a certain agenda, you have just endorsed their ideology. You may not believe in their cause but by helping them defeat their enemies, you have just helped them further their beliefs, by their ability to instill them in the population you leave when the job is done. Big Boss genuinely attempts to be careful in which jobs he chooses to take, being conscious of the effects of his participation. Over time, this choosing inevitably gives shape to MSF’s ideology, whether they choose to accept it or not. In MGS:Peace Walker, by accepting Paz’s request to investigate the mysterious army occupying Costa Rica, it ultimately leads Big Boss/MSF to take an “anti-nuke” position (an understandable position). How can a brotherhood without ideology take a stance, such as anti-nuke? Because BB and Kaz deny this inherent flaw, they lose control of the ability to choose their ideology, instead being susceptible to the ever-changing flow of global politics. This is how by the end of Peace Walker, MSF (a group that’s anti-nuke proven by its actions) now possess their own nuclear equipped Metal Gear. The final cutscene (here it is if you need it) of Peace Walker shows BB and Kaz discussing the fact that they’ve inadvertently taken sides and an identity, but they double-down and convince themselves their inherently flawed concept is still achievable. MGSV shows them facing the harsh consequences of their denial, and by them placing the blame for MSF’s destruction on Skull Face rather than accepting their own delusions, it shows they are still lost. To reiterate, I believe the phantom pain is the loss of their dream that the killing of Skull Face cannot replace. This is where I somehow find a way to defend the duplicated missions we’re forced to play through in MGSV’s Act 2, something I never expected myself to do. I was just as furious with the repetition as most players, and I quickly fell into the notion that these missions were re-used because the game was unfinished. A quick google search and few videos on YouTube were all it took for me to buy into the conspiracy that Konami didn’t let Kojima finish the game and rushed its release, Kojima-be-damned! And if I’m being honest, I never finished mission 46. I half-heard the twist ending, thought it was a lame Shyamalanian cop-out, and called it good. I made peace with the 75ish hours I’d put into the game. “It was fun” I thought, “and I’m content to leave it at that.” It wasn’t until a few months ago that I finally decided to return to the game and see the true ending for myself. The year and a half break from the game, combined with seeing the ending with my own eyes, gave me the perspective to appreciate the story Kojima chose to tell with MGSV and think about it in new ways. Or I should say, to think about the game for myself, rather than finding myself lost in the rip-tide of the internet’s meme concerning the game. What I mean is that I acknowledge this is just my read on the game, and it may or may not have been Kojima’s intent. Ultimately though, I believe Kojima makes many elements of his game ambiguous, to force his players to make their own reads and take their own stances on them. So this is mine… Mission 51 was obviously unfinished and cut from the game, but that doesn’t mean Act 2 was also unfinished. Rather, the duplicated missions in Act 2 were intended to convey monotony and dissatisfaction, because the revenge on Skull Face could never fix what haunted Venom Snake, Big Boss, and Kaz. Skull Face was never their demon, they were their own demons. His actions merely made them face the reality of their flawed interpretation of The Boss’ will. After re-creating their dream through Act 1, we now find them carrying on business as usual, left as disappointed as we the players are, that killing Skull Face didn’t achieve anything substantial. But that can’t truly be what Kojima intended right? He wouldn’t pull a stunt like this, potentially sacrificing some of the fun of his own game, just to convey a theme right? To answer those questions, simply remind yourself of MGS2… doesn’t it become a little more clear in that context? Kojima is absolutely willing to take chances, because he wants to create strong reactions in his players, even if they’re unhappy ones. It’s safe to say that Act 2 created a strong reaction, and re-assessing my reaction, as well as that of the fanbase, was the only way I came to my understanding of the game. And there lies Kojima’s genius. He’s powerfully communicated the themes of PAIN and REVENGE to me in a memorable way, even though I’ve already largely forgotten the specifics of MGSV’s plot. We, the players, truly experienced phantom pain even though many of us have never lost a limb. We built up these expectations of what Big Boss’ bloody revenge and fall to the dark side would look like. We fantasized about it and created epic scenarios in our head that would close the book on MGS and tie up all loose ends. In some ways it’s fair to blame trailers for the game like THIS ONE, for hyping up the game’s narrative unrealistically (although who knows how much input Kojima had on the direction for those trailers... EDITORS NOTE: Since writing the article, Kev learned Kojima famously edits all his trailers, so it technically is Kojima's fault...) But in other ways, we need to be honest that we didn’t need a trailer to hype us up unrealistically for a new Metal Gear Solid game. We already expected an epic conclusion before a trailer could create an expectation for one. To blame the game’s marketing for our issues with it, is like BB & Kaz blaming Skull Face for the issues with MSF that were always there. I encourage every MGS fan who hates MGSV to reconsider it. Now that you’ve had time away and some room to breathe, you may be surprised at what you find when you return. Now, understand I’m not trying to minimize the game’s flaws. Yes, those helicopter loading sequences take entirely too long. Yes, the inclusion of Psycho Mantis is forced and preposterous. Yes, Quiet’s character design is despicable (which personally meant I didn’t feel comfortable taking her on missions. D-Dog is dope though, so I never felt underpowered, even if Quiet is possibly the stronger ally) and the pseudo-scientific explanation justifying her lewd design is extremely dumb, but she’s actually an empowering character from a purely narrative perspective. She’s the one character who chose not to take revenge, and through her actions proved that your identity can be determined without language. Maybe that’s enough to bring you around on the character, or maybe not. I’m not saying all the game’s issues were intentional, rather, maybe the issues were worth what we got. The point is, the game has proven to be endlessly rewarding for me… but I almost missed it. To end this loquacious and overlong analysis (if you made it this far, you can make it through Phantom Pain again), this game was the key that I feel helped me finally understand Kojima. He’s one of the few game creators willing to say something with his games. Even more rare, he’s willing to put you at odds with a game so you’ll have to reflect on what he’s trying to say. Ever since MGS1, he’s been trying to teach his players to think for themselves (for instance: “what’s important is that you choose life…and then live!”) I believe this is the #1 overall message he’s tried to impart to his players throughout all his games. Maybe MGSV: The Phantom Pain is a bad game… I think Kojima would defend your right to think that. When I think about it for myself though, here’s my take… MGSV has greatness, and I was wrong when I didn’t see that.To read the article where it was originally published: https://letsgetfrivolous.tumblr.com

My Problem with Rey vs Kylo: Written by Mike (Originally posted: Feb. 26th, 2016) First off…Spoilers….duh. Now before anyone starts off with the “You just can’t stand a strong independent woman winning a fight against a male antagonist” accusation…. hold your outrage and hear me out. I love the idea of a plucky junkyard-planet urchin rising from obscurity and realizing a level of prowess in the force that shocks even Luke Skywalker. The fact that she has no Y chromosome (I’m making assumptions about humans in a Galaxy Far Far Away) is an added bonus because its fresh and more inclusive. What I don’t like, however, is a lack of consistency in the universe’s governing rules and the fact that Ray is made straight up over-powered. Don’t agree? Well let’s compare notes then. As far as we know, Rey has NOT received any force training up until this point. She’s 19 years old and thus far hasn’t been schooled in the finer points of sensitivity, meditation, or application of the force. Hell, she doesn’t even really know IF it exists or not. Admittedly the whole “He’s too old” trope has been lampooned and stepped on throughout the entire Star Wars series (more so in the orig-trige than in the prequels). The comparatively old Luke Skywalker, who essentially was brimming with force swirling destiny, barely had the ability to tap into the perception powers of the force after a few hours of sessions with Obi-Wan Kenobi. These were actual tutoring sessions in which direct effort, focus and advice were provided and still Luke didn’t demonstrate any telekinesis or force persuasion abilities in the same time table as Rey. Anakin, the literal CHOSEN ONE, with a higher…yuck….“medichlorian count”….than Yoda could merely fly his podracer/starships with slight precognitive abilities from au natural force use. Rey totally blows the future Darth Vader out of the water in terms of natural abilities. This in and of itself would be fine if the dialogue/writing alluded to this kind of ability in ANY way beforehand. How hard would it be to have someone she interacted with mention a strange luck that Rey is known for or that she’s good at “negotiating” her way out of tight spots. We’re talking 3-4 seconds of extra dialogue at most. But we have no inclination of this latent potential. Other people may mind that she knows starfighter engines but I buy that someone who has to pick through Star Destroyer hulls in order to eat will either learn how to be a star-mechanic or starve. I’ll even gloss over the “she talks to aliens and droids so she should be able to speak Shrywook and Binary”. The ace pilot thing doesn’t make sense either…but again, I’ll gloss over it. These things are a bit hokey but for some reason I didn’t mind or notice them. As many people would point out, Luke never had any explicit backstory inserts that he was already an ace pilot; the movie only stated he wanted to attend the academy. Let’s fast forward to the part where she finds the “excali-sabre”. I wasn’t a fan of lightsabers “having a soul/destiny/will of their own” choice already, but fine, the more elegant weapon of a more civilized age can now grant visions. It’s odd that it wouldn’t have given the son of its creator visions but…okay I digress. After this point and a few sentences of “you gotta shut your eyes and feel the light” talk from Maz we now see Rey taking her first steps…out the door. There’s no sitting and finding herself in the presence of another force user to guider her or anchor her. She dips. That’s it. All I would want out of this scene was a few seconds of Maz (who may be a bit sensitive herself I couldn’t tell if that was what Abrams was trying to convey) moving Rey along. It would have totally fit that she sensed Kylo Ren approaching and freaked. God knows I probably would have. Let’s now jump ahead to the force sadism chair scene. Kylo Ren, grandson of Vader and nephew and heir to Luke and has had training from both the only surviving Jedi Master and what I assume is the new trilogy’s equivalent of a Sith Lord, is trying to Spanish Inquisition his Uncle’s location out of Rey. This interaction is another that a few people I’ve talked to had a few issues with. I’m actually totally cool with Rey catching Ren off guard and going on the offensive. The specificity of “not as powerful as Darth Vader” was a little wonky but I like the idea of Rey’s latent abilities engaging as a fight or flight defense mechanism for her mind. What I didn’t like was the almost from left field force persuasion demonstration against the storm trooper afterwards. If ANYONE had mentioned that this was a thing I’d be perfectly happy. Anyone. If Han Solo had told a whacky story, if Maz had mentioned it, if Rey had said that she “heard of crazy Jedi powers” etc., if any of these 3-4 second things had happened in dialogue you wouldn’t hear a peep from me. But, as if Rey had seen a New Hope, she tries the ol’ Jedi mind trick. Now we get to the actual point. I’m not mad or surprised that Finn and Rey managed to defeat Kylo. After all, he took a freaking bowcaster bolt to the torso. I’m reading into the situation a bit, but I would imagine ALOT of his concentration and force powers are going towards just keeping himself conscious and his organs intact. This makes the playing field much more level in terms of Ren’s ability to use the force in combat a la choking, lightning, etc. Where I start to think deus ex machina is when Rey is able to out-telekinesis Ren when he’s pulling the lightsaber. I have no issue with someone who knows how to use “force pull” out pulling Kylo when his attention and abilities are split. What I have an issue with is Rey instinctively and randomly knowing how to use the force in that way. When Luke pulled force pull out of his hat it was a supreme act of desperation, he was LITERALLY reaching for something he couldn’t grasp and this manifested in the force embodying his will. The metaphor for concentration, focus, and willpower overcoming intense adversity is much deeper and more resonant. In the instance Rey pulled the sabre towards her, I wasn’t so much as “Hell yeah! She’s dope!” I was more like…“Really? When did she learn to do that?” Now I will admit openly: I am an EU (now Legends) fanboy. I have way too much invested time and knowledge of specific force characteristics, techniques, names, times, and details. As such I will grant that I am nitpicking here a tad.

But in a way, I’m really not. As previously stated, it’s almost as if Rey herself has seen A New Hope, and is the embodiment of our childlike selves trying the Jedi Mind Tricks and the Force pulls that she saw Luke do. Again, if someone, ANYONE, had mentioned any of these specific traits and abilities of the force until now I would not care. The story would flow the same way and then any nit-picking would in fact be born of misogyny or Luke-fanism. For me the suspension of disbelief was hampered a little bit and I was again reminded that I was watching a movie, something that didn’t really happen on Luke’s journey. Now to be fair, good old JJ had a HUGE task on his hands and it must have been absolutely stressful to try to write a TFA that was engaging for new fans and nostalgic enough for returning audience members. The hype train definitely carried this work a bit though and I don’t feel bad making that claim. I want to really like Rey and I want to fanboy out on how awesome she is. She has the potential to be a really deep and interesting character and possible abandonment issues could definitely be a dark side pull in the future. Her interactions with a possibly reluctant Luke would be even more compelling harkening back to a Yoda-esque “you must train me!” I’m still pumped for the next episode and none of what I mentioned was world breaking. But ladies and gentlemen, I believe we are at the point where female characters don’t need to overcompensate for the “girlness” by being OP or maguffiny in their capabilities. Luke needed Han and Leia for specific roles in the first three and it feels like Rey (as Kev my cohost for my podcast pointed out) is Luke, Han, and Leia all rolled into one. I think that Rey is a compelling enough character that she can be vulnerable and mortal and she will still be beloved as the New Hope (pun intended). At the end of the day there may be plot fill in, recap, and twists that negate everything I’ve said…and that would make me happy. When Kev and I were discussing what Rey’s fatal flaw was I determined that if I had to pick it would be naiveté or over-optimism. It takes a special kind of gullibility/faith/loyalty/denial to believe that your family was returning to Jakku a decade plus change later (I’m not calling her stupid by the way it could be that she instinctively clung to a hope that while not realistic still kept her going). This may in fact explain EVERYTHING. Once she learns that she has force abilities she assumes/believes/zens her way into awesomeness because she has utmost faith in herself and who she is. That would be a great metaphor for self-actualization and self-validation, something that everyone including young women in our society could definitely benefit from. If that’s the plan, writers of Episode VIII, please take a few seconds to write it in. I can’t wait to see it! To read the article where it was originally published: https://letsgetfrivolous.tumblr.com |

ArchivesCategories |